Gerald Donnellan

Jerry Donnellan is a true native New York hero. He was born on December 28th, 1946 in Nyack, New York to Irish-American parents. He is the youngest of five children, all of whom attended Albertus Magnus High School in Rockland County. He went on to go to Rockland Community College and then transferred to Texas A&M soon after to major in English.

Jerry came from a military family. His father was in the U.S. Navy during World War II, his oldest brother was in the Air Force during the Korean War, and his middle brother served in Germany during the peacetime of the 1950’s. During Jerry’s youth, veterans of both the Spanish-American War and World War I were still alive to tell their stories. He was inspired by the heroism of those who had gone before and served their country.

During the height of the escalation in the Vietnam War, Jerry was drafted into the Army, in July of 1968. Despite his doubts about the war, the strong love he felt for his country resolved him to set aside any uncertainty. His military career began in Fort Gordon in Georgia with Basic Training. Reflecting back on his Basic Training experience, the comic strip character Beetle Bailey inevitably pops into his mind, “dodging his sergeants and peeling potatoes.” It was not until Advanced Individual Training (AIT) at Fort Jackson in South Carolina that the reality and seriousness of what they were training for hit him.

Specializing in Infantry, he was placed into the 11- B-10 Battalion. From AIT, he went to Fort Benning in Georgia to non-commissioned officer school to become a sergeant. He was then shipped back to Fort Benning to serve as a drill sergeant, figuring it was better to be the hunter than the hunted. “It was a strange feeling. Here I was back at Basic Training, the same location where but a few months before I was being initiated into the Army. This time, however, I was the one responsible for training the recruits.”

After spending several months at Fort Benning, Sergeant Donnellan received orders to deploy to Vietnam. He took the orders with mixed emotions, a strange combination of apprehension and relief. “In a way, I had been waiting for the deployment orders. Back then, everybody in the service shipped out to Vietnam sooner or later. It might as well be sooner.”

From the air the Vietnamese countryside with its lush green mountains and fertile valleys looked like the Ramapo or Catskill Mountains of his native Hudson Valley. When he landed, he found himself in Cam Ranh Bay, a deep water port near the South China Sea, which served as one of the United States military’s point of entry and departure. He felt surprised at how relaxed and un-warlike it seemed there. “It was a very casual atmosphere, almost like a bizarre Boy Scout camp.”

In addition to the Army hospital, Cam Ranh Bay hosted the Air Force Tactical Fighters and cargo airlift operations, and was a Navy port as well. Jerry soon found out that Cam Ranh Bay, located towards the rear of the American lines, did not reflect the real horrors of fighting against the enemy.

Sergeant Donnellan spent three days adjusting to Vietnam, learning about booby traps and the Vietcong’s guerilla warfare tactics. After the training, his unit was moved from the peaceful sanctuary in the rear to the brutal reality of the front lines. Flung into this new environment in such contrast with Cam Ranh Bay, his training was quickly put to the test against the North Vietnamese Army and its non-conventional tactics. To Sergeant Donnellan it felt as though he was a policeman walking a beat in a lethally dangerous neighborhood where the criminals took advantage of every hiding place and knew all the tricks of the terrain. The fighting resembled more a television show than a classic war, “American cops versus Vietcong gang members.” Following a battle, the Vietnamese would remove their dead from the field to prevent accurate death counts to chip away at American morale. “We would fight against the [Vietcong] all day, but at night, when we went to see how many we killed, we wouldn’t find any bodies. It made us think our own losses had been for nothing…. They were a shadow enemy who knew how to play mind games against us naïve teenagers who didn’t have a clue.”

On October 24th, 1969 Sergeant Donnellan and his unit were marching up Hill 370 when sniper fire rang out, followed by a heavy barrage of Vietcong artillery. The soldiers fought their way up the hill through heavy enemy fire. The enemy held the high ground and were shooting down upon the advancing American Army. Mortars were raining all around the troops storming the hill. Early in the fight, Sergeant Donnellan was hit with mortar fire from a round that landed nearby. The shrapnel caused a flesh wound, which he bandaged up before continuing up the hill and into the thick of the fighting. Halfway up the hill, an enemy grenade exploded nearly at his feet. It was the loudest thing he had ever heard. He had the sensation of flying as he was thrown through the air.

The blow left him dizzy and disoriented. Once his head finally cleared, he tried to assess his injuries. His right arm hung limp at his side with a double compound fracture, held together only by a few pieces of muscle. With his left hand he tried to feel his lower body. His left leg felt as if it had been shredded to bits, his lower right leg was gone, and he was blinded from the blood dripping from a deep head wound.

The medic came quickly, but in the darkness Sergeant Donnellan didn’t know if he was friend or foe at first, which only added to his distress. Jerry was injected with a dose of morphine to relieve the pain. He was evacuated to the rear as soon as the Army was able to bring in a helicopter. He was taken to a MASH unit, an area in the rear designated as a temporary army hospital. The drugs altered his memory of time, but he distinctly remembers the coldness of the hospital. For the first time in months, he was in an air-conditioned building.

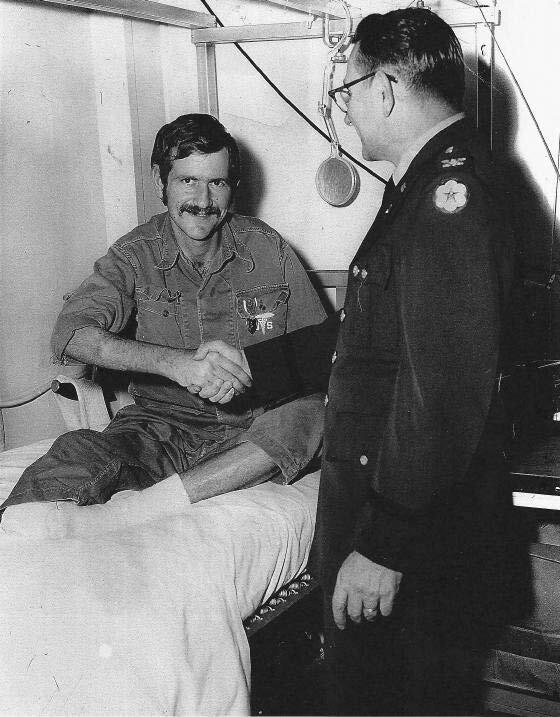

Colonel Grant pinned the Purple Heart onto Sergeant Donnellan’s shirt.

It took five days of surgery, but the doctors were able to save his life. He was transferred to the Army hospital in Japan, then to Fort Dix and finally on to Valley Forge in Pennsylvania where he spent a year in physical therapy, not far from that special place, so hallowed in America’s memory, of sacrifice and suffering during the winter of 1777-1778, where Washington and his soldiers faced an uncertain fate with courage and resolve. How fitting it was to be awarded his Purple Heart in Valley Forge. He was awakened at 6 a.m. by one of the nurses, who had a special visitor in tow. Grumpy at having been woken up so early, he recalls pulling the hospital blanket over his head, while giving expression to his feelings with some choice “colorful” language. It was only when the blanket was pulled away from his head did Sergeant Donnellan recognize the eagle worn on the Army uniform of Colonel Dan Grant. While Jerry was stammering out an apology, Colonel Grant pinned the Purple Heart onto Sergeant Donnellan’s shirt.

After he was discharged from the hospital, he returned home to the Hudson Valley. He, like many other soldiers returning home from a warzone, found it difficult to readjust to civilian life. Battle-hardened, he saw the world now through different lenses. He found he seemed to have different values and a different perspective from his civilian peers back home. War had taught him the truly important aspects of life, and he had no longer any room for petty complaints or the superficial concerns of civilian life which we can let blind us to what is truly important.

Knowing firsthand the problems and difficulties faced by veterans led Jerry to his current position as Veterans Affairs Director for Rockland County. His mission in Veterans Affairs is to bridge the gap between veterans and society, a gulf which he believes to be much wider today than in years past due to the seeming remoteness of war and its harsh realities in the national consciousness. His office is full of intriguing memorabilia and military lore: photos, antique equipment, model planes, tanks, and even a Civil War Minié ball. Each item in his office is a conversation piece that Jerry uses to connect with his veterans.

Through him, as well as numerous other veterans organizations, society is searching to find ways to give back to those who have given so much. For Jerry Donnellan, who has already sacrificed so much for his country, working at Veterans Affairs is his way of continuing to help the heroes of today readjust to their civilian life of the future. 53