Daniel Gade

“Soldiers who have not been to war want to go to war. Soldiers who have been to war, don’t want to. They go because it is their duty,” expresses Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Gade, a two-time Purple Heart recipient, and instructor at West Point. “There is little glory in war, and whatever glory there is, is far outweighed by the horror of war.”

Daniel Gade was born February 7, 1975, in Minot, North Dakota. His parents were farmers as well as schoolteachers. He was the middle child, the third out of five children. From a young age he was taught the meaning of patriotism from his father, a veteran of the Vietnam War. Daniel’s middle name is MacArthur. His older brother is named Patton. Their uncle was a West Point graduate, Class of 1975.

Raised on the farm until the age of sixteen, he always loved being outdoors. “I had a wonderful childhood. We worked hard, taking care of the animals. But there was always plenty of time to play as well.” There was little interest for television in his family; play meant his dog, his BB gun, and the local 4-H club.

Dan always knew he wanted a military career. He was accepted into the United States Military Academy at West Point out of high school. Dating back to the American Revolution, the fortifications at West Point, designed by the Polish military engineer Thaddeus Kosciuszko in 1778 overlooking the Hudson River, played a main strategic military role. President Jefferson signed the legislation in 1802 establishing it as the United States Military Academy. “I always expected to serve. I always expected to go to West Point.”

Thanks to Daniel’s childhood in the outdoors, he had little trouble adjusting to the rigorous requirements of the elite academy. He found the college to be a very rewarding experience. “West Point is a wonderful place, a great place to learn how to be a leader and a soldier.” The cadets’ experience in the 1990’s was a little different than today. “It was harder in some respects. There was less interaction between plebes and upper classmen, and what interaction there was was sometimes painful. But always, the same emphasis on learning how to be a leader.”

Gade graduated as a 2nd lieutenant in 1997, commissioned as an armored officer. He was assigned to 3rd Regiment, 2nd Armored Division, stationed at Fort Carson, Colorado. He served in Colorado for three years, got married, and attained the rank of captain, before being accepted as an exchange student in the Marines Amphibious Warfare School. Shortly before September 11, 2001 he was selected to attend Army Ranger School.

Building on the tough, hard-core modern concepts of light infantry training under extremely difficult situations, Army Ranger School is a leadership school. “It trains you to lead others under stress, duress, food and sleep deprivation. It’s an endurance and grit school where you learn how to inspire and lead soldiers so that the stress of combat won’t seem as foreboding as it would otherwise have been… the difference being that in training you never have the feeling you are about to die. In combat you often get the feeling you are in grave danger and that you could die.”

From December 2001 to August 2004 Captain Gade was deployed in Korea north of Seoul just thirty miles south of the Demilitarized Zone. “The Koreans are lovely people, very friendly, very kind. It was a great experience.” At first a staff officer with the 1st Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division, in 2003 Captain Gade received the honor of being selected to command a tank company. “Our primary mission was to deter North Korean aggression… it was a real world mission.”

They were deployed to Iraq in August 2004, two tank companies and the 2nd Infantry Division. His thoughts when he learned they were going to Iraq? “That’s what I trained for. I was excited, I was scared… I felt our mission in Iraq was very worthwhile.” They landed first in Kuwait on August 7. After one week they transferred over to Iraq. By the first week of September 2004 the 2nd Infantry Division was operating in hostile terrain.

As a company commander, Captain Gade was placed in charge of four platoons, totaling one hundred twenty men. At every moment in Iraq, at least one of his platoons was always out in the field on assignment. A platoon would either be out on a mission, returning from a mission, resting, or getting ready to go out on a mission. Captain Gade would often go with his men on their missions. His credo: this is what measures a leader, and that is why he is placed in that position. His leadership skills in combat are meaningless if he is not alongside his soldiers. “As an officer I’ve always felt that my place was to be out where the danger was most likely.”

What were the Iraqi people like in this area? “Our region was all Sunni. The main insurgency came from the Sunni people, Al-Qaeda is a Sunni organization. Half the people were hostile, not actively but passively hostile, acting as though cooperating but not telling us the truth. The other half were scared for their lives, afraid to be seen as cooperating with Americans. It was a very complex situation….”

A typical day would see them out at 9:00 in the morning. Captain Gade would try to visit every command post, until 3:00 the next morning. “The most likely time for an attack was early evening or late at night. We would leave base camp to visit local tribal leaders. We often went out on foot patrols, talking to people and scouting the local areas. We were in ththe midst of creating a tactical phone book, filled with detailed information about our surroundings. We needed to know all the information down to who lived in each house. The thing is, you never know when someone will attack you. You’ll go from walking in a neighborhood to being engaged in a firefight.”

On November 10, 2004, Captain Gade and his men were out on a tank patrol. “Someone fired [a] Rocket Propelled Grenade. Normally the RPG does little damage to the armor on the tank. This one struck the hatch on the top of the tank, the hatch soldiers use to enter and exit the vehicle. The rocket struck our loader, Dennis Miller, killing him instantly.” Gade was near him, in the tank. He received shrapnel wounds in the arm and face. His injuries were not severe, and he returned to duty immediately. Each new day, however, brought new danger.

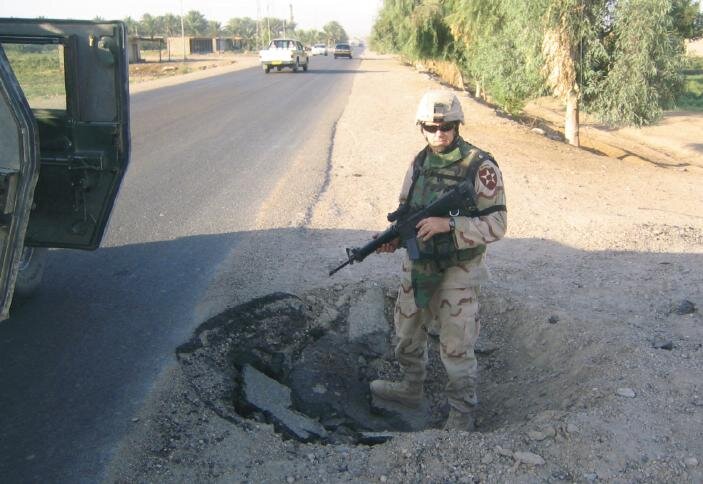

“On January 10, 2005, I was riding in a Humvee, going out to talk with local tribal leaders. I had talked to one already and was heading out to talk to another. [The next thing I recall] I woke up, on my back, in a ditch. [I was told later] we had driven over a roadside bomb, which exploded. I was in the passenger seat when it went off….I remember hearing somebody screaming and some shouting and I tried to crawl to who ever w a s screaming because your first response is to help… the soldiers around me said, ‘Settle down, Sir’ and then I realized I was the one who was hurt.” His soldiers managed to drag him out of the Humvee. He had massive wounds to his legs and abdomen. While a medic worked to stop the bleeding, another officer called in a medevac helicopter. Gade was flown to the U.S. Navy’s surgical station, where Dr. Chambers performed the first of many surgeries to save Gade’s life. After being stabilized, Captain Gade was flown to Baghdad, still sedated, where further operations were performed, before being sent to Germany for still more surgery. He needed urgent kidney dialysis. Within 24 hours, the Army flew him to the Walter Reed Army Hospital, in Washington D.C. It was here that Gade awoke. It was January 30th, almost three weeks later.

“One of the things we commonly think is that people who are sedated are in a peaceful state and are not aware. But that’s not true. I had nightmares, very violent dreams, Al-Qaeda coming into the hospital… in my dreams I thought I lost both my legs, maybe other body parts. When I woke up, I was pleasantly surprised to find that I had lost only one leg…. I was pleased to be alive.”

But it was still unclear to his doctors whether Gade would live. He suffered from serious infections, and still had heavy bleeding. He required massive blood transfusions. He was in a neck brace and hooked up to oxygen tanks.

He was to remain in the hospital for five months, his wife Wendy and parents by his side. Both Dan and his wife turned thirty while he was in the hospital, his wife while he was still unconscious; his birthday came when he was still in intensive care. She prayed fervently the entire time, “and with great effect.” It was their faith that kept them hoping and believing. After several months, and multiple surgeries, the doctors announced that Gade would make it. Still, they kept him in the hospital for another month. When he was discharged, he lived at Fischer House, an outpatient home near the hospital. He was there for six months, recuperating and learning to adapt to his new right leg, a prosthetic device.

Before his injury, Daniel had been accepted into the University of Georgia. After recovering, he completed his Master’s Degree in Public Policy and Administration, then worked at the White House for one year, in the Veteran’s Administration, before earning his Ph.D in the summer of 2011. He accepted a teaching position at West Point, and has since enjoyed instructing West Point cadets in the same manner of excellence for which West Point has been known throughout its existence.

“I enjoy the cadet drive for excellence and their patriotism. I get a chance to teach and shape the leaders of the United States Army, and these future leaders of the United States. The cadets will continue to accomplish great things long after I’m finished.

“The biggest thing, and the hardest to teach to young cadets, is that military service is not about themselves. It’s about laying down your life for others. I think that my injury helps to teach them that. I think too when they see me limping around it helps to drive home to cadets that the military is a dangerous profession.” It is a commitment, to serve and defend America regardless of the personal price.

Patriot Gade attained the rank of major in 2006 and was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 2013. However, it is not about rank or accolades. “Greatness is not measured by what a man or woman accomplishes, but by the opposition he or she has to overcome to reach their goals.” Daniel Gade has never let his injuries Daniel Gade has never let his injuries hold him back in life. He is a triathlon athlete, having competed in the Iron Man competition of 2010, involving a 2.4 mile swim, a 112 mile bike race, and a 26.2 mile run.

Lieutenant Colonel Gade has never forgotten the man who saved his life many years ago. Every year, on January 10, Daniel calls up Dr. Chambers, the physician who performed Gade’s first surgery. Like LTC Gade, Dr. Chambers has twin boys, and is a devout Christian. They always talk about their families, their faith and their lives since the incident. Above all, Daniel enjoys spending time with his family, competing in physical challenges, and teaching West Point cadets. When asked if he would change anything about his life, knowing what he knows now about the realities of war, he says simply, “I would not change a thing.” It is not rank. It is not prestige. It is not recognition that defines who a person is. It is character.